This historic and renegade outdoors magazine took two long absences from publishing, but it’s now back under new ownership. Here’s why that’s cool.

From the beginning, Mountain Gazette has always been the kind of magazine that publishes stories that other publications won’t run. Think of it like the alt weekly of outdoor rags. Got a soliloquy about pickled food jars in Western dive bars or a meditation on biking naked through town? That’s a Mountain Gazette story. Over the years, the publication has featured contributions from storied writers like Edward Abbey, Hunter S. Thompson, Dolores LaChapelle, Dick Dorworth, and Royal Robbins.

Born in 1966 and originally called the Skier’s Gazette, it was never just about skiing. Mike Moore, the publication’s first editor, reportedly taught a course at a Denver community college on literature and drinking, where he met students at a different bar each week to discuss legendary works of writing.

“Moore asked me to write a piece about a Joan Baez concert I had attended in Berkeley, which is a long way from skiing and even mountains; but it suited the publication and the Vietnam era time of protest and social questioning and change,” author and skier Dick Dorworth wrote in a piece about the history of the publication. “He liked the Baez concert piece and after that he asked that I write about anything that came to mind as often as I wanted.” So, Dorworth did, penning stories on subjects like driving at night, climbing Half Dome, tripping on acid, Buddhism, and more.

Readers of Mountain Gazette have always had a loyal fondness for the publication, collecting old issues like antiques or framing magazine covers for their walls. The magazine ran stories that felt irreverent, bold, and unapologetic. To poke fun at the top-10 lists often found in glossy, ad-driven magazines, the Gazette once ran a story on the best mountain towns to get your ass kicked in. A photo essay on scenic highways in Colorado had pictures of roadkill in every image. Long-form narratives—we’re talking 30,000-word manuscripts—have always been the magazine’s specialty.

A man named Gaylord Guenin took over as editor after Moore and moved the publication’s home base to Boulder, Colorado. But business at the Gazette wasn’t great—Edward Abbey allegedly used to send checks in with his submissions—and by 1979, the magazine was dead, leaving a hole in the publishing market for esoteric meanderings related to life in the mountains.

“There was no place to publish 100-page manuscripts, no place to counter the perspective found in the slick outdoor/outside/manly macho journals and magazines that cater to image rather than substance and to the advertising dollars of the industry of recreation above all else rather than to the soul and heart of mountain living, mountain recreation, mountains walking for those with the eyes to see,” writes Dorworth.

In 1983, Mike Moore and others set about reviving the Gazette, but nothing panned out. Then, in 2000, a free-spirited writer named M. John Fayhee officially resurrected the Gazette, putting out the first issue in almost 20 years and making it a free monthly. He kept the publication alive, eventually selling the title to the Colorado-based publisher Summit Publishing Co., which also put out a free magazine called Elevation Outdoors. But then the Mountain Gazette went dark again in 2012, with the then-publisher citing dwindling advertising revenue as the main reason for the closure.

Mike Rogge

Mountain Gazette would remain obsolete for another eight years, until a former Powder and Ski Journal editor named Mike Rogge decided to bring the title back yet again, inking a deal to buy the magazine in January 2020. “I ran into limitations working for other people,” Rogge says. “It’s a classic entrepreneur story. I figured why not do it on my own?”

By March of 2020, at the beginning of the Covid pandemic, 30 boxes of old Mountain Gazette issues showed up at Rogge’s home in Tahoe and he had something to read while quarantining at home. “I really liked that people felt comfortable baring their souls in the pages,” he says. “I liked how long Mike Moore let people write. I liked how every story felt completely unique and that uniqueness was the vibe of Mountain Gazette. It was never a heavy-handed narrative edit. I like to hear the writer’s voice and not the title’s voice. That really connected with me. I liked how they were irreverent. It felt like the National Lampoon of outdoor writing.”

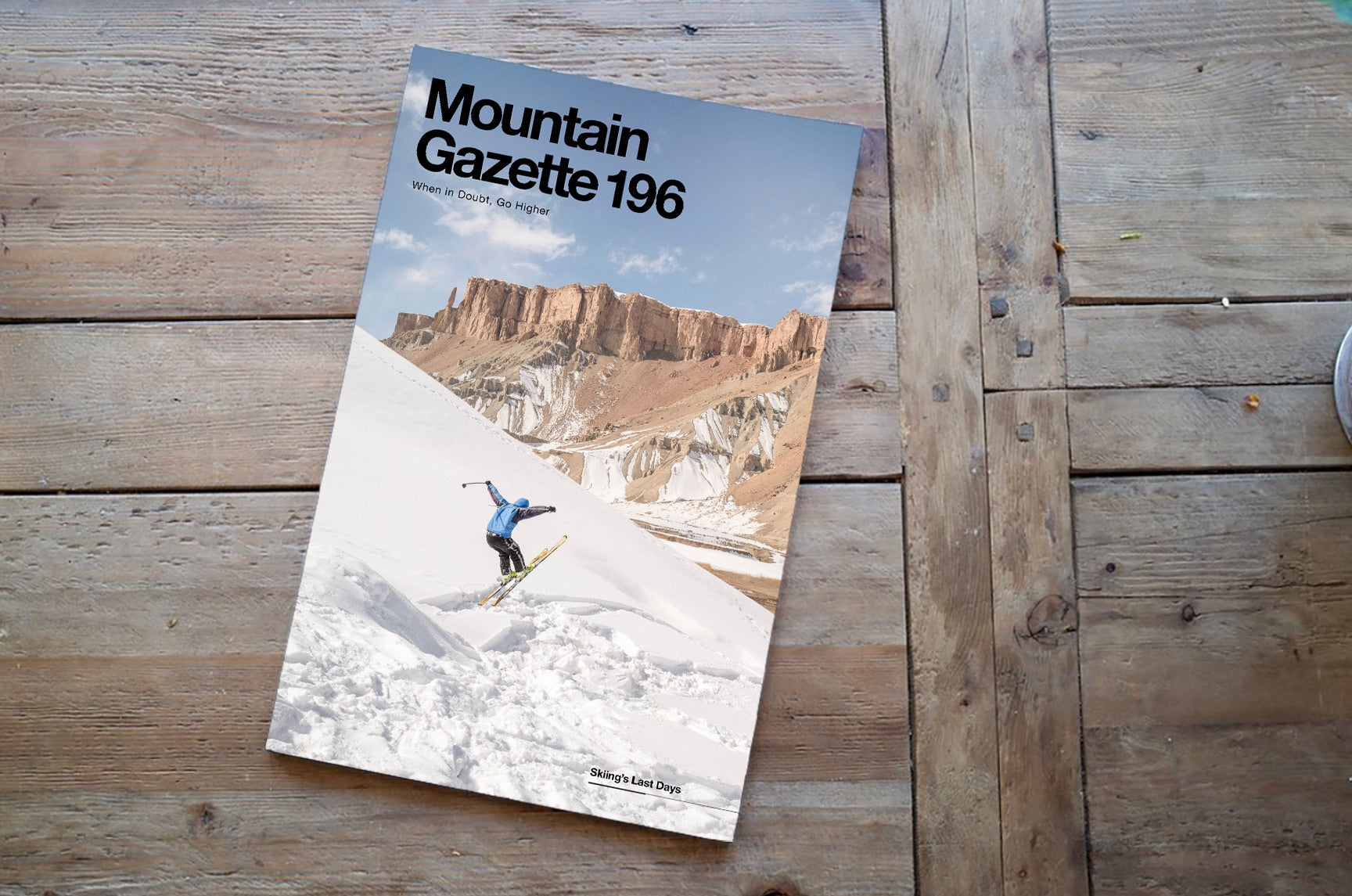

Now, Mountain Gazette is printed twice a year in a large 11-inch by 17-inch format. (One reader complained that it was too big to bring on an airplane, which it is.) Subscriptions cost $60 a year and though advertising exists, the business model is set up to rely more on dedicated subscribers than on advertisers. (Flylow, full disclosure, is one of those advertisers). The magazine currently has 3,000 subscribers, some of whom are readers who subscribed to the original version back in the ’60s.

“I have worked for a lot of different publications, both in and out of skiing, and what I found is that they are all kind of stuck in their ways,” Rogge says. “As far as how they delivered their subscription or how they treated their readers, it felt like everyone was leaving the reader as the least important aspect. I want to make a reader focused magazine.”

Rogge hopes to continue the legacy of making Mountain Gazette the alternative publication for the outdoors. “It’s always been about the people who identify as outdoor people,” says Rogge. “Our editorial mission now is to cover the stories that happen when you walk out your front door. That allows us to broaden the type of people who can write and shoot for us. It doesn’t look out of character to have a hardcore ski story next to a story about coyotes in Los Angeles or a birdwatcher in New York City.”

This is not a magazine you pick up and flip through casually in five minutes. It’s meant to live on your coffee table and capture the feelings of a moment in time, to represent a culture of people drawn to the mountains for their own individual reasons. “Our magazine is not meant to help you run a marathon, or tell you what to eat or what to buy,” Rogge says. “What it’s meant to do is be this living embodiment of your values. It’s meant to make you think.”